Archiving Experience (ISEA 2010)

This paper looked at the implications of the third version of the Variable Media Questionnaire, an online database designed to help understand how an artwork may be best preserved when its initial form decays or expires. VMQ 3.0 introduced a shift from the previous two versions by viewing the fundamental unit of an artwork as not the artwork itself, but the pieces that go into its construction. In an attempt to capture as many impressions of the work as possible, questions about those components are posed to not just the artist whose name is on the wall next to the piece but also the curators, conservators, assistants, and even viewers who have experienced the work. But the modern reality of art is that it is not enough to treat an artwork as just a collection of physical parts, and so the VMQ also recognizes environments, user interactions, motivating ideas, and external references as aspects to be surveyed and considered when preserving or recreating the piece. Expanding the scope of the data collected by the questionnaire changes the focus of preservation from an artwork’s materials to its experiential characteristics, potentially exposing perspectives on the works it describes that had not been previously considered and pushing the VMQ into a new role as an epistemological prism through which art can be viewed.

Notes from the presentation, part of the “Still Accessible? Rethinking the Preservation of Media Art” panel, are below. Proceedings are available on the ISEA2010 site.

The Third Generation Variable Media Questionnaire, v1.1

June 18th, 2011

VMQ2

To start, I’d like to briefly reintroduce the second version of the Variable Media Questionnaire. The VMQ is a framework for understanding how to preserve works that are subject to decay and obsolescence.* It begins with the assumption that material works–remembering that digital code is ultimately stored on material somewhere–have a finite life span. So, while efforts to preserve an original work are useful, ultimately the question is going to become what should happen once to the work once that is no longer viable. That’s obviously a loaded question, and subject to many different answers from any number of people who are associated with the creation and display of the work. What the VMQ does is provide a model to begin asking the questions, and ultimately to record the answers to those questions when they’re posed to the various stakeholders involved.

In the second version, the VMQ’s framework was built around medium-independent behaviors and strategies. You can see the behavior categories in the tabs at the top of the screen. Each behavior that can be attributed to a work has a number of questions associated with it that describe the work as it exists, either now or in an “ideal” state. Once those questions have been answers it suggests another set of questions that are based on preservation strategies that are appropriate for the work given its behaviors. I’d like to show you a bit more about how it worked, but unfortunately the VMQ2 itself has fallen victim to what it’s trying to work around: it was made in a version of Filemaker Pro that no longer runs on my machine, so I’m limited to showing you documentation of the work instead of the work itself.

While the VMQ2 model is still useful, what we’ve found is that there are also some limitations. The biggest one is that there is limited flexibility in the model, which means that there is a limit to the specificity of the questions it suggests. Since each behavior has a fixed set of questions and options, it can be difficult to apply VMQ2 to a work that is outside the boundaries of its original conception. Even though the goal is to find medium-independent qualities in a work, each work is still going to be individual and will inevitably either have some pieces that don’t have relevant questions in the model or have questions in the model that don’t apply to the work. In addition, the implementation of the VMQ2 makes it difficult to answer questions about similar parts of a work that may require different strategies for preservation, like the television monitors and plants that make up Paik’s TV Garden.

VMQ3

The third versions of the VMQ addresses these issues by adjusting the underlying epistemological model of the questionnaire. The new focus for the questionnaire is flexibility, which it achieves by addressing an artwork less as a whole than as a set of parts* that are configured with specific relationships to one another. While the behaviors and strategies of VMQ2 are still part of VMQ3, they are now embedded at a lower level. Instead, the top hierarchical level for an artwork are the components from which it is built.

We didn’t just cut this schema from whole cloth. It is based on the way software is built from classes of objects in object-oriented programming. Each part of a work can be considered an instance of an abstract class of parts: a 42″ plasma screen is an instance of a media display, for example. Within an artwork, some parts may be modifiable within certain specifications: some artists may not care if you replace their 42″ plasma screen with a 50″ LCD. Interviews in the questionnaire are used to determine how much latitude can be applied to each part of a work. But as long as the updated version is within the same class of components, the questionnaire treats it the same as the original. As a result, these abstract parts are really functional logical components of the work that may or may not map directly to the physical components you see when the pieces is displayed or stored.

The best way to explain this is to show an example.*

This is Octris, a project I’m working on this summer that is going to be part of the Without Borders Festival in Maine when I get back. It is a 3 dimensional Tetris variant with a twist; over time the visuals fade away and the player has to position pieces only using audio cues that they learn before the graphics disappear. The director of the VEMI Lab where I’m developing this software researches functional equivalence, particularly non-visual perception of spatial information. Of course, my first instinct upon arriving there was to make a 3D Tetris game that could be played by people who are visually impaired.

If I were to break this project down into its physical components, it might look something like this. Octris uses a computer with some software I wrote, a monitor, a head mounted display, and a Wiimote:

Structure of an Artwork

Translating the work into VMQ3 terms and creating an interview requires a bit more analysis than physical components, however*. First I want to show you how data is structured in the VMQ. (Click on “VMQ Organization above.) A work has a stakeholder and a set of components. Each component has questions associated with it that are important to consider when attempting to preserve the piece. In turn, each of those questions has a set of pre-defined potential answers, usually corresponding to the preservation strategies that were central to previous versions of the VMQ. Once the piece has been put into this structure, an interview logs the interviewer, interviewee, and the selected responses to each question.

Functional Components

Functional components are not equivalent to physical ones, even if you add digital or virtual components like software. The idea is that each component fulfills a certain role in the overall scheme of the work. The variable media paradigm is always looking to the future, and in the future these roles may not be fulfilled by the same technology as they are now, but they will all need to be fulfilled somehow in order to recreate the experience of the original work.

The breakdown this time is quite a bit different. Although the headset is a single physical piece, it’s actually fulfilling two roles in the system of the work because it is both an audiovisual output and an input for accelerometer data that is capturing the movement of the player. The player himself is a necessary component of the system as well, in this case classified under the VMQ component ‘participant’. Computer hardware and software are pretty much the same as they were, but the Wiimote in the player’s hand is now considered functionally equivalent to the accelerometer in the headset because they are both inputs controlled by the player. The computer monitor becomes a second media display because it is functionally similar to the output hardware in the headset.

There are two more VMQ components I’m going to use when I add this artwork to the database that have no real equivalents in the physical breakdown. The first is the spatialized system. I’m including this as a component because I think that virtual reality worlds have a set of preservation questions associated with them that are specific to that system and won’t be handled by the generic “custom software” or “media display” components. It is essentially a special case of custom software, but one that comes with enough preservation issues that I think it warrants its own component. However, it doesn’t replace custom software, it adds to it, or acts as an overlay for it.

The second non-physical VMQ component I’m including is “Key Concept”. In this case, there is a concept that is central to the purpose and construction of the work””I want to translate the visually displayed spatial information in this 3D Tetris variant into a form that can be interpreted using only audio. Any attempt to reconstruct this piece once its original technology is obsolete needs to respect that core concept; at least in the eyes of the original designer.

Building a VMQ3 Work

Now that I’ve broken the project down into these functional components, I can actually start to add the work to the VMQ. I do that by logging in and going to the big plus sign up in the corner, then hitting the artwork icon. First it asks a few preliminary questions – title, year, etc.

One thing you’ll notice is that, after I type in the title of the piece, the panel goes into a hold mode for a moment and then pops up a message that says a new Metaserver entry will be created. I’ll talk about that more in a minute because it is a minor point as far as this particular artwork is concerned, but the Metaserver our answer to the ongoing issue of data sharing within these sort of applications. For now, though, all it tells us is that that title isn’t already a part of the Metaserver. I’ll give it a quick description…

Next is creator. In the VMQ data scheme, there can only be one ‘Creator’ of a work, and it must be one of a class of VMQ objects called stakeholders. Groups or collaborations are treated as individual stakeholders for the purpose of naming a creator, but stakeholder objects can be related together so that individual people can be named as members of a collective, for example. In this case, I’m the creator, so I just have to find my stakeholder object and drag it over to the artwork.

Now I can add all the components from my functional breakdown before. They are:

- Key Concept

- Software, Custom

- Computer Hardware

- Media Display (HMD)

- Media Display (Monitor)

- Participant

- Participatory Interface (Accelerometer)

- Participatory Interface (Wiimote)

- Spatialized System

But there’s a problem. When I search for Spatialized System, I don’t get anything back because that component doesn’t exist in the database. This is where the flexibility of the new VMQ comes in; if it doesn’t exist already, I can create one on the fly. That shouldn’t be necessary very often; in fact, it defeats some of the purpose of the VMQ’s structure if every tiny part is given its own specific component, so it is not something that should be done lightly. The biggest question is: does this component have a set of preservation issues that requires different questions than the components already in the system? If I decide that it’s necessary, I can go back up to the add icon and put in a component. Components are built the same was as artworks, just one level down the heirarchy, so I can also create a set of new questions and answers that are relevant to this component. If I were doing this for real, this would be where I’d have to sit down and think for a bit about what sort of questions apply to this component generically, and not just in the specific instance of this artwork. For example, though it isn’t relevant here, one question might be “How should changes to the physical install space be represented in the spatialized system?” with a number of different answers corresponding to different preservation strategies. In the interest of time I’ll just put in one answer for now and move on.

When I hit submit on that the question I just added appears down in the corner here, ready for use. I can drag it over to the component, finish out the component, and submit that, then add the new component to the artwork.

Adding an Interview

Once I have the artwork created, I can open it up and add a new interview. Here there are a number of general questions to answer, a place to list who the participants in the interview are and what roles they played, and the option to restrict access to a certain user or institution for those who do not want to share the interview publicly. After that are all the components and questions, ready to be answered.

I’m not going to go through the entire interview, but there are a couple of key things that I want to point out. The first is the Interview Participants section. The VMQ doesn’t just limit interviewees to the original artist; it expects that any number of people associated with the work will have valuable insights into how that work is experienced. The original artist or their estate may be interviewed, but it could also be an assistant who helped in the works’ production, a curator who worked with the piece in an exhibition, or even a visitor off the street who experienced the work. Now, that doesn’t mean that all of these interviewee’s opinions would have to be considered equally. The person who is responsible for the works’ preservation may decide that a random museum-goer’s perspective deserves a different amount of weight than the original artist’s, but the VMQ itself is agnostic to that and is intended to simply make as much data available as possible.

The second piece that I want to point out is the response section. Each of the questions has the answers that were added to it when the question was created, but responses are not limited to just one of the answers. Multiple answers, with different strengths or preference levels, can be given for each question. In addition, if there is a question that is not currently a part of the component””say somebody tries to use the dummy Spatialized System component I just created with only one question and answer””the components, questions, and answers can all be retroactively edited. Those edits are propagated to all other artworks that use the same components or questions as well, so everybody can benefit from one person’s additions.

The Metaserver

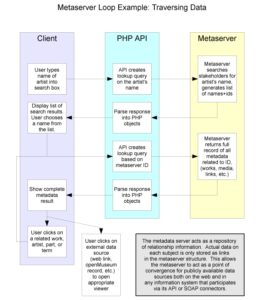

So far I’ve given you an overview of the VMQ itself, but there is one piece that I mentioned before that I want to go back and talk about for a moment: the Metaserver. The VMQ3 was created as part of the Forging the Future coalition, which built a set of related but independent tools that cover different aspects of preservation. One of the ongoing issues that crops up with all of these separate tools is finding data across services. The VMQ is intended for Variable Media data, but if I want a catalog of the physical pieces that go into Octris I have to put that into a different database. The Metaserver was designed to be the way to follow those threads between different systems.

When the artwork panel popped up the message that Octris doesn’t exist in the Metaserver it wasn’t looking in the VMQ’s own database, it was doing a search of the Metaserver. The Metaserver itself is only designed to hold the minimum amount of data necessary to uniquely identify a work or stakeholder, along with a set of pointer to data stored in other systems. It is designed to transparently integrate into the tools that access it; by adding Octris as an artwork to the VMQ, I simultaneously added it to the Metaserver. If somebody using another database that integrates Metaserver support searches for it, not only will the find that Octris is already registered on the Metaserver but they’ll also find a link that takes them directly to the VMQ record for the project. For example, I know that TV Garden is registered in the Metaserver because it has a VMQ record. If I open TV Garden’s record, though, I can see that it also has a record in another system, The Pool. Clicking that link takes me directly to TV Garden’s Pool record, where I can see that The Pool contains data on reviews of the piece and its thematic antecedants and descendants.

The Metaserver is one of those small bits of infrastructure that can potentially have a large impact on use. The VMQ itself is a web service, so””subject to the restrictions put on data when it is entered””the data is viewable by anyone who visits the website. However, there are any number of databases out there that are like the second version of the VMQ: isolated local installs of a database, with data that is siloed away and completely dark to the rest of the world. If those databases are built on systems that can run web queries and be connected to the Metaserver, the data in them doesn’t have to be dark. Other institutions, academics, artists, and researchers can see that museum X has a record on piece Y. Depending on the level of integration the data itself may not be directly accessible, but at least the knowledge that the data exists opens the doors to sharing it and making it relevant outside of the sphere of an individual institution. Even within an institution, linking data in disparate databases that all have a different focus could be very useful by itself.

Conclusion

I’d like to finish up my portion of the presentation by mentioning that I don’t really think of the VMQ as just a preservation tool, but more as a structure that can be used to look at many different aspects of how a piece comes together. For example, when I was putting together this record for Octris, I had to figure out how to classify the two input devices, the accelerometer and the Wiimote. My first instinct was to make two different components, an interface device component for the Wiimote and a sensor component for the accelerometer. But after I thought about it I realized that, as far as the system of the work was concerned, they are really the same type of component. They are both interfaces for capturing the actions of the player, it’s just that we think of them differently because we’re actively controlling the Wiimote buttons but the accelerometer is just collecting data about an action that we consider to be natural when the player moves his head to look around. That bit of insight, which may be obvious but I at least had never really thought about before, is probably going to change how I build the VR interfaces at this lab. So just by applying a VMQ analysis, even without doing any actual preservation work on the piece itself, I learned something new…and I think there’s a great deal of value in that. VMQ3 is an application of a model to build a database, but I think the model itself is where the most interesting part of the work lies.

Notes

- All of them, for a long enough time scale.

- I’m using the terms “component” and “part” interchangeably here. The VMQ calls them “components” right now, but for external data standardization reasons we’re transitioning to using the term “part”.

- This demo was done live at the ISEA panel. If you’d like to try it yourself, please go to the VMQ’s demo site.

- This explanatory Flash video by Jon Ippolito may help, at least until Flash disappears.